Types

Table of contents

Checking Program Invariants Statically

As programs grow larger or more subtle, developers need tools to help them describe and validate statements about program invariants. Invariants, as the name suggests, are statements about program elements that are expected to always hold of those elements. For example, if we write x : number in our (to be developed) typed language, we mean that x will always hold a number, and that all parts of the program that depend on x can rely on this statement being enforced. As we will see, types are just one point in a spectrum of invariants we might wish to state, and static type checking—itself a diverse family of techniques—is also a point in a spectrum of methods we can use to enforce the invariants.

In this module, we will focus especially on static type checking: that is, checking (declared) types before the program even executes. You might be familiar with this from your prior use of Haskell or Java. We will explore some of the design space of types and their trade-offs and learn why static typing is an especially powerful and important form of invariant enforcement.

Consider the following program in a typed version of our language. We will define the full language later, but the example should be simple to understand.

(let ((f (λ (n : int) : int

(+ n 3))))

(f #t))

Our type system should be able to flag the type error before the program begins execution. The same program (without the type annotations) in ordinary Racket fails only at runtime:

(let ((f (λ (n)

(+ n 3))))

(f #t))

But before we define our typed language, we will have to understand what are types.

Note: Complete implementation of the code shown in this unit can be found in the types implementation on GitHub.

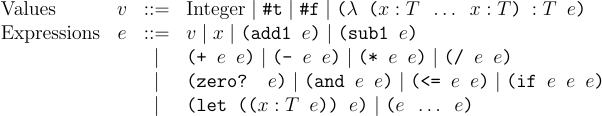

Concrete Syntax

The general syntax of the typed language is shown as below. It is same as the language with lambda functions, except for places where new variables are introduced. So lambda function have type annotations attached to each argument and finally another type to denote the type of value it produces. The other place we need types are let bindings.

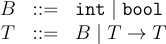

Before we proceed we still have to describe what types (the T in the above figure) are. Types can be base types for constants like int and bool in our language. They can also be function types denoted by the arrow. The last type in the function type (T) is the type of value computed by the function and anything preceeding it are the arguments (T1 through Tn). Thus, int -> bool is a function that takes an integer and produces a boolean, while int -> int -> int is a function that takes two integer arguments and produces an integer.

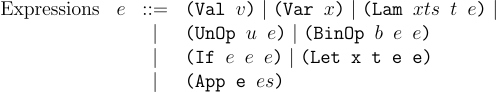

Abstract Syntax

To handle these changes in the surface syntax, we have to extend our AST and the parser. The AST is updated such that Lam now contains xts which is list of argument identifiers and their types and an additional t which is the return type of the function. Likewise, the t paramater in Let stores the type of the identifier being declared.

To represent these changes we add the new fields to Lam and Let structs. To represent types, we use the struct T to denote base types such as int or bool. Functions are represented as FnT where args is the list of arguments types and ret is the return type of the function.

(struct Lam (xts t e) #:prefab)

(struct Let (x t e1 e2) #:prefab)

(struct T (t) #:prefab)

(struct FnT (args ret) #:prefab)

Then we updated our parser to pattern match against the x : T syntax. The newly defined parse-type function converts the surface syntax of the types to our structs. It maps int and bool to (T 'int) and (T 'bool). For function types it recursively parses all the types and creates a FnT struct.

(define (parse s)

(match s

[(? integer?) (Val s)]

[(? boolean?) (Val s)]

[(? symbol?) (Var s)]

[(list (? unop? u) e) (UnOp u (parse e))]

[(list (? binop? b) e1 e2) (BinOp b (parse e1) (parse e2))]

[`(if ,e1 ,e2 ,e3) (If (parse e1) (parse e2) (parse e3))]

[`(let ((,x : ,ty ,e1)) ,e2) (Let x (parse-type ty) (parse e1) (parse e2))]

[`(lambda (,@xts) : ,t ,e) (Lam (parse-xts xts) (parse-type t) (parse e))]

[`(λ (,@xts) : ,t ,e) (Lam (parse-xts xts) (parse-type t) (parse e))]

[(cons e es) (App (parse e) (map parse es))]

[_ (error "Parse error!")]))

(define (parse-xts xts)

(match xts

['() '()]

[`(,x : ,t) (cons (list x (parse-type t)) '())]

[`(,x : ,t ,@rest) (cons (list x (parse-type t)) (parse-xts rest))]))

(define (parse-type t)

(match t

['int (T 'int)]

['bool (T 'bool)]

[`(-> ,@ts ,ret) (FnT (map parse-type ts) (parse-type ret))]

[_ (error "Unhandled type")]))

Now that we’ve fixed both the term and type structure of the language, let’s make sure we agree on what constitute type errors in our language (and, by fiat, everything not a type error must pass the type checker). Here are a few obvious forms of type errors:

- One or both arguments of

+is not a number, i.e., is not a(T 'int). - One or both arguments of

*is not a number. - The expression in the function position of an application is not a function, i.e., is not a

FnT. - The expression in the function position of an application is a function but the type of the actual argument does not match the type of the formal argument expected by the function.

A natural starting signature for the type-checker would be that it is a procedure that consumes an expression and returns a type for it. If it cannot, it will throw a type error. Because we know expressions contain identifiers, it soon becomes clear that we will want a type environment, which maps names to types, analogous to the value environment we have seen so far.

Type checker

Just like our interpreter, the type checker pattern matches on the AST and type checks each AST node.

(define (tc TE e)

(match e

[(Val v) (tc-val v)]

[(Var x) (lookup TE x)]

[(UnOp u e) (tc-unop TE u e)]

[(BinOp b e1 e2) (tc-binop TE b e1 e2)]

[(Let x t e1 e2) (tc-let TE x t e1 e2)]

[(Lam xts t e) (tc-lam TE xts t e)]

[(App e es) (tc-app TE e es)]))

We will look at these individual cases below, but how do we use the type checker? All we have to do is call it before we begin the evaluation of our program. So our interp-err function is updated to:

(define (interp-err e)

(with-handlers ([Err? (λ (err) err)])

(begin

(tc '() e)

(interp '() e))))

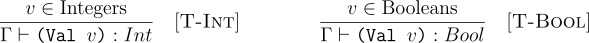

For values, our type checker see if the constant is an integer or boolean returns the corresponding type.

The judgment here says in the type enviroment Γ, the expression (Val v) has the type Int if v is an integer and boolean if v is a boolean. In our implementation we use TE to denote the type environment. The type of an expression always follows the :. Written in code this looks as below:

(define (tc-val v)

(match v

[(? integer?) (T 'int)]

[(? boolean?) (T 'bool)]

[_ (error "Unexpected value")]))

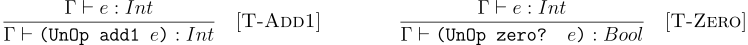

For unary operations like add1 and sub1, an integer is produced only if the argument to these is an integer. Similarly, zero? produces a bool only if it’s argument is an int.

Just like our interpreter, any type derivation in the premise becomes a recursive call. Thus for unary operations, our type checker looks like this:

(define (tc-unop TE u e)

(match* (u (tc TE e))

[('add1 (T 'int)) (T 'int)]

[('sub1 (T 'int)) (T 'int)]

[('zero? (T 'int)) (T 'bool)]

[(_ _) (error "Type error!")]))

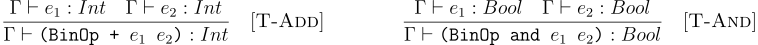

For binary operations, similarly our type checker should check that the type of all subexpression is an expected. Below are shown the rules for the + and and operations.

Notice the types for and: we are now defining that both operands need to be booleans and and will produce a boolean. This was not in fact how we defined and in our interpreter! Our underlying language can handle all types of arguments (both integers and booleans) passed to and. However, by restricting the types to booleans, we are restricting the behavior of the language. This is an important characteristic: type systems can change the semantics of the language and our interpreter should behave soundly with respect to the interpeter.

(define (tc-binop TE b e1 e2)

(match* (b (tc TE e1) (tc TE e2))

[('+ (T 'int) (T 'int)) (T 'int)]

[('- (T 'int) (T 'int)) (T 'int)]

[('* (T 'int) (T 'int)) (T 'int)]

[('/ (T 'int) (T 'int)) (T 'int)]

[('<= (T 'int) (T 'int)) (T 'bool)]

[('and (T 'bool) (T 'bool)) (T 'bool)]

[(_ _ _) (error "Type error!")]))

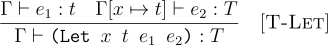

For let, it is analogous to how it is interpreter, but instead of interpretation, we just need to call the typechecker, while at the same time checking the computed type of the bound expression is the same as the annotation.

(define (tc-let TE x t e1 e2)

(if (equal? (tc TE e1) t)

(tc (store TE x t) e2)

(error "Type error!")))

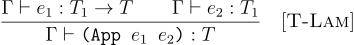

Lambdas when type checked will always return a function type. Below is the formal rule to type a lambda term (for only one function argument). The body of the lambda is type checked by binding the variable in the type environment.

(define (tc-lam TE xts t e)

(if (equal? (tc (append xts TE) e) t)

(FnT (map last xts) t)

(error "Type error!")))

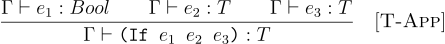

Conversely, function application expects the first term to be the function, i.e., have a function type. All other terms are checked to have correct argument types, in which case the entire application expression is given the return type of the function.

(define (tc-app TE e es)

(match (tc TE e)

[(FnT args ret) (if (equal? args (map (λ (e) (tc TE e)) es))

ret

(error "Type error!"))]

[_ (error "Type error!")]))

After this, you might wonder type checking and interpretation are very similar, but there are some key differences. For example, from the perspective of type-checking (in this type language), there is no difference between binary operations like +, -, *, and /, or indeed between any two functions that consume two numbers and return one. For such operations, observe another difference between interpreting and type-checking. Arithmetic operations care that the arguments be numbers. The interpreter then returns a precise sum or product, but the type-checker is indifferent to the differences between them: therefore the expression that computes what it returns int is a constant, and the same constant in both cases.

Observe another curious difference between the interpreter and type-checker. In the interpreter, application was responsible for evaluating the argument expression, extending the environment, and evaluating the body. Here, the function application case does check the argument expression, but leaves the environment alone, and simply returns the type of the body without traversing it. Instead, the body is actually traversed by the checker when checking a function definition, so this is the point at which the environment actually extends.

Type checking conditionals

We did not discuss if until now, even though it is a part of our language. Even the humble if introduces several design decisions. We’ll discuss two here:

- What should be the type of the test expression? In some languages it must evaluate to a boolean value, while in other languages it can be any value, and some values are considered “truthy” while others “falsy”.

- What should be the relationship between the then- and else-branches? In some languages they must be of the same type, so that there is a single, unambiguous type for the overall expression (which is that one type). In other languages the two branches can have distinct types, which greatly changes the design of the type-language and -checker, but also of the nature of the programming language itself.

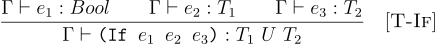

This can lead to a variety of rules in our language. The following rule says, the condition expression will always have to be a boolean, and both branches have to be the same type:

(define (tc-if TE e1 e2 e3)

(match* ((tc TE e1) (tc TE e2) (tc TE e3))

[((T 'bool) t2 t3) (if (equal? t2 t3) t2

(error "Type error!"))]

[(_ _ _) (error "Type error!")]))

This is followed in Java, but it can turn out to be restricting for type systems for programs that return values of different types on different branches. A popular solution is to extend the language of types to add union types. This involves adding a form T U T to the syntax of types. These union types can be represnted using a UnionT struct:

(struct UnionT (t1 t2) #:prefab)

Union types denote a value can be either of type t1 or t2, and there is no way to tell statically which one it will be be. Then we can define union as an operation that given two distinct types can merge them into an union type and handles if with branches producing different types.

(define (union t1 t2)

(if (equal? t1 t2)

t1

(UnionT t1 t2)))

(define (tc-if TE e1 e2 e3)

(match* ((tc TE e1) (tc TE e2) (tc TE e3))

[((T 'bool) t2 t3) (union t2 t3)]

[(_ _ _) (error "Type error!")]))

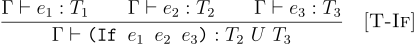

Another alternative design could be to relax the restriction on branch condition to be a boolean just like our untyped language. In such a case, the language evaluates the conditional at runtime to decide if an expression is truthy or falsy and then evaluates the corresponding branch.

(define (tc-if TE e1 e2 e3)

(match* ((tc TE e1) (tc TE e2) (tc TE e3))

[(_ t2 t3) (union t2 t3)]

[(_ _ _) (error "Type error!")]))

Thus something as simple as type checking if can involve a lot of decision of about ther language semantics and the type system.

Recursion

Now that we’ve obtained a basic programming language, let’s add recursion to it. The simplest recursive program is, of course, one that loops forever. Can we write an infinite loop with just functions? We already could simply with this program:

((λ (x) (x x))

(λ (x) (x x)))

which we know we can represent in our language with functions as values.

But now that we have a typed language, and one that forces us to annotate all functions, let’s annotate it. The first subexpression is clearly a function type, and the function takes one argument, so it must be of the form t1 -> t2. Now what is that argument t1? It is the type itself. Thus, the type of the function t1 -> t2 which expands into (t1 -> t2) -> t2, which further expands to ((t1 -> t2) -> t2) -> t2, and so on. In other words, this type cannot be written as any finite string! If we cannot write the type, we will never be able to expression this program in our typed language in the first place.

Program Termination: The typed language we have so far has a property called strong normalization: every expression that has a type will terminate computation after a finite number of steps. In other words, this special (and peculiar) infinite loop program isn’t the only one we can’t type; we can’t type any infinite loop (or even potential infinite loop). A rough intuition that might help is that any type—which must be a finite string—can have only a finite number of ->’s in it, and each application discharges one, so we can perform only a finite number of applications.

If our language permitted only straight-line programs, this would be unsurprising. However, we have conditionals and even functions being passed around as values, and with those we can encode any datatype we want. Yet, we still get this guarantee! That makes this a somewhat astonishing result.

This result also says something deeper. It shows that, contrary to what you may believe—that a type system only prevents a few buggy programs from running - a type system can change the semantics of a language. Whereas previously we could write an infinite loop in just one to two lines, now we cannot write one at all. It also shows that the type system can establish invariants not just about a particular program, but about the language itself. If we want to absolutely ensure that a program will terminate, we simply need to write it in this language and pass the type checker, and the guarantee is ours!

What possible use is a language in which all programs terminate? For general-purpose programming, none, of course. But in many specialized domains, it’s a tremendously useful guarantee to have. For instance, suppose you are implementing a complex scheduling algorithm; you would like to know that your scheduler is guaranteed to terminate so that the tasks being scheduled will actually run. There are many other domains, too, where we would benefit from such a guarantee: a packet-filter in a router; a real-time event processor; a device initializer; a configuration file; the callbacks in single-threaded JavaScript; and even a compiler or linker. In each case, we have an almost unstated expectation that these programs will always terminate. And now we have a language that can offer this guarantee—something it is impossible to test for, no less!

Typing Recursion: What this says is, now we must make recursion an explicit part of the typed language with form letrec.

(letrec ((fact : (-> int int) (λ (n : int) : int

(if (zero? n) 1

(* n (fact (- n 1)))))))

(fact 5))

for the factorial function fact, where n is its argument, and int the type consumed by and returned from the function. The expression (fact 5)represents the use of this function.

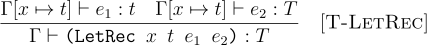

How do we type such an expression? Clearly, we must have n bound in the body of the function as we type it (but not of course, in the use of the function); this much we know from typing functions. But what about fact? Obviously it must be bound in the type environment when checking the use ((fact 5)), and its type must be int -> int. But it must also be bound, to the same type, when checking the body of the function. (Observe, too, that the type returned by the body must match its declared return type.)

Now we can see how to break the shackles of the finiteness of the type. It is certainly true that we can write only a finite number of ->s in types in the program source. However, this rule for typing recursion duplicates the ->` in the body that refers to itself, thereby ensuring that there is an inexhaustible supply of applications. It’s our infinite quiver of arrows.

The code to implement this rule would be as follows:

(define (tc-letrec TE x t e1 e2)

(if (equal? (tc (store TE x t) e1) t)

(tc (store TE x t) e2)

(error "Type error!")))

Type soundness

We have seen earlier that certain type languages can offer very strong theorems about their programs: for instance, that all programs in the language terminate. In general, of course, we cannot obtain such a guarantee (indeed, we added general recursion precisely to let ourselves write unbounded loops). However, a meaningful type system—indeed, anything to which we wish to bestow the noble title of a type system—ought to provide some kind of meaningful guarantee that all typed programs enjoy. This is the payoff for the programmer: by typing this program, she can be certain that certain bad things will certainly not happen. Short of this, we have just a bug-finder; while it may be useful, it is not a sufficient basis for building any higher-level tools (e.g., for obtaining security or privacy or robustness guarantees).

What theorem might we want of a type system? Remember that the type checker runs over the static program, before execution. In doing so, it is essentially making a prediction about the program’s behavior: for instance, when it states that a particular complex term has type int, it is effectively predicting that when run, that term will produce an integer value. How do we know this prediction is sound, i.e., that the type checker never lies? Every type system should be accompanied by a theorem that proves this.

There is a good reason to be suspicious of a type system, beyond general skepticism. There are many differences between the way a type checker and a program evaluator work:

- The type checker only sees program text, whereas the interpreter runs over actual stores.

- The type environment binds identifiers to types, whereas the interpreter’s environment binds identifiers to values or locations.

- The type checker compresses (even infinite) sets of values into types, whereas the interpreter treats these distinctly.

- The type checker always terminates, whereas the interpreter might not.

- The type checker passes over the body of each expression only once, whereas the evaluator might pass over each body anywhere from zero to infinite times.

Thus, we should not assume that these will always correspond!

The central result we wish to have for a given type-system is called soundness. It says this. Suppose we are given an expression (or program) e. We type-check it and conclude that its type is T. When we run e, let us say we obtain the value v. Then v will also have type T.

The standard way of proving this theorem is to prove it in two parts, known as progress and preservation. Progress says that if a term passes the type-checker, it will be able to make a step of evaluation (unless it is already a value); preservation says that the result of this step will have the same type as the original. If we interleave these steps (first progress, then preservation; repeat), we can conclude that the final answer will indeed have the same type as the original, so the type system is indeed sound.

For instance, consider this expression: (+ 5 (* 2 3)). It has the type int. In a sound type system, progress offers a proof that, because this term types, and is not already a value, it can take a step of execution—which it clearly can. After one step the program reduces to (+ 5 6). Sure enough, as preservation proves, this has the same type as the original: int. Progress again says this can take a step, producing 11. Preservation again shows that this has the same type as the previous (intermediate) expressions: int. Now progress finds that we are at an answer, so there are no steps left to be taken, and our answer is of the same type as that given for the original expression.

However, this isn’t the entire story. There are two caveats:

- The program may not produce an answer at all; it might loop forever. In this case, the theorem strictly speaking does not apply. However, we can still observe that every intermediate term still has the same type, so the program is computing meaningfully even if it isn’t producing a value.

- Any rich enough language has properties that cannot be decided statically (and others that perhaps could be, but the language designer chose to put off until run-time). When one of these properties fails—e.g., the array index being within bounds—there is no meaningful type for the program. Thus, implicit in every type soundness theorem is some set of published, permitted exceptions or error conditions that may occur. The developer who uses a type system implicitly signs on to accepting this set.

As an example of the latter set, the user of a typical typed language acknowledges that vector dereference, list indexing, and so on may all yield exceptions.

The latter caveat looks like a cop-out. In fact, it is easy to forget that it is really a statement about what cannot happen at run-time: any exception not in this set will provably not be raised. Of course, in languages designed with static types in the first place, it is not clear (except by loose analogy) what these exceptions might be, because there would be no need to define them. But when we retrofit a type system onto an existing programming language—especially languages with only dynamic enforcement, such as Racket or Python—then there is already a well-defined set of exceptions, and the type-checker is explicitly stating that some set of those exceptions (such as “non-function found in application position” or “method not found”) will simply never occur. This is therefore the payoff that the programmer receives in return for accepting the type system’s syntactic restrictions.

These notes are adapted from CS173 at Brown.