Mutation and State

Table of contents

Imperative languages

Until this point in the class, we developed a pure functional programming language, i.e., you could create and pass functions around or apply them to other values. More importantly, all computations were expressed as function applications—arguments went in and the computed value was returned. This is a general model for expressing all kinds of computations, but it might still feel limiting. Many of you are used to imperative languages (like C or Python), where instead of function applications being nested, you are used to a sequence of statments that execute with the program. The goal of this module is to learn how to model such languages and understand how they work.

The key thing in these language is an implicit state. As the language executes individual statements, the statements compute a return value and/or modify this implicit state. Contrast this with our functional language where the only thing computed is the value returned, there is no state hidden away from the programmer like what happens in imperative languages. Through the following sections we will look at how we add state to our program.

Note: Complete implementation of the code shown in this unit can be found in the state implementation on GitHub.

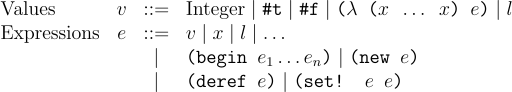

Concrete Syntax

First, we extend the surface syntax to write programs that have sequences of instructions. So we can write programs like below:

(begin

(add1 45)

(let ((x 42))

(+ x 3))

#t)

Here, the begin block describes a sequence of actions to be evaluated. The result of the entire begin block is the result of the last statement, and all intermediate results are discarded. However, if all intermediate results are discarded there is no use of writing a sequence of statements! To access results of previous statements in a program, one needs to add to the language the ability to store and retrieve results of prior computations.

In its simplest form, storage is a place to put things so we can go back and get them. Storage can come in many forms - tape, disk, memory, USB sticks, firmware - but it always allows for values to persist in some form over time. Storage can be viewed abstractly as a collection of locations that are values for storing other values. Think of a location as a box and the value at a location as the contents of the box. The location is a value in the sense that it is constant and does not change, but the contents of a location can change. We dereference a location when we want the value it stores. Remember, a location is a value and as such can be calculated and returned without affecting the contained value. Dereferencing gets the value out and returns it.

Storage exists in the background and is there to use whenever needed. When we program we declare variables, pointers and references that all reference storage, but we don’t ever talk about storage as a whole unless we’re systems programmers. In C this means accessing the heap memory (using malloc and free), or in languages like Python it just means the memory managed by the language runtime.

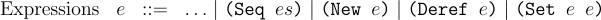

To do access store, we add to the language 3 constructs: new, deref, and set!. new allocates a fresh location in the store. Think of this as allocating some new memory and putting the result in that location. deref derefences a given location to return the value stored in that location and set! updates the location to store a new value. Thus our previous language is now extended to have the following forms:

Here is an example of a program using the store:

(let ((x (new 5)))

(begin

(set! x (add1 (deref x)))

(+ 3 (deref x))))

This program creates a new location to store 5 and binds x to this new location. Following that, it runs a sequence of statements, where it updates the value stored in the location contained in x to 6. Finally, it adds 3 to the updated value. This computation should return 9 as a result. Notice, as x is a reference now, we have to use deref to dereference the value from the location stored in x.

Abstract Syntax

We will define new structs for the AST corresponding to the new additions we made to the concrete syntax. The grammar for the AST nodes look like:

Defining the new structs, our AST definition looks like:

#lang racket

; other definitions not shown

(struct Seq (es) #:prefab)

(struct New (e) #:prefab)

(struct Deref (e) #:prefab)

(struct Set! (e1 e2) #:prefab)

Notice, we did not add a new struct for the locations, as they will be created at runtime and there is no way for the programmer to add a location to the source text. We will update our parser to now handle these extensions to our language:

;; S-Expr -> Expr

(define (parse s)

(match s

; rest of the cases omitted

[`(begin ,@es) (Seq (map parse es))]

[`(new ,e) (New (parse e))]

[`(deref ,e) (Deref (parse e))]

[`(set! ,e1 ,e2) (Set! (parse e1) (parse e2))]

[_ (error "Parse error!")]))

Meaning of state

Now we are ready to give precise meaning of programs that handle state. We model state as a global store that maps locations to their values. This is a very abstract model of state, but it is one of the most general ways to model it. If you are concerned the environment sounds just like the state, then you are right—they have a lot of similarities, but the biggest one is the state is mutable. The global state can change as the program is executing. In other words, as programs were evaluated before they only produced a value, but now evaluation of programs will require an initial state and once evaluated it will yield a final state and the value produced from the computation.

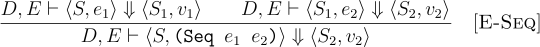

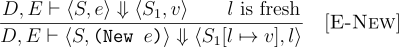

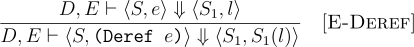

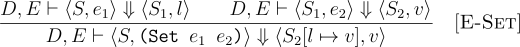

To write this we will change the judgement of our formal rules. Now our judgment will look like D, E ⊢ ⟨S, e⟩ ⇓ ⟨S, v⟩. This means under a given set of definitions D and environment E, our rules take a tuple of the initial state S and expression e and evaluate it the final state S and a value v.

The meaning of (begin e1 e2) is to execute e1 and e2 in sequence. The state evolves through the computation and is used for evaluating e2. The entire block evaluates to the meaning of e2. The rule can be extended for any number of expressions inside begin.

The meaning of (new e) is to allocate a new location in the store, and store the meaning of e in that location. The newly allocated location is the meaning of (new e).

The meaning of (deref e) is to dereference a location in the store, and get the value stored at that location.

The meaning of (set e1 e2) is to get the location to be updated from the meaning of e1 and the value to be updated to from e2 and update the location from e1 to the meaning of e2.

Through all these operations the state might change because any subexpression may modify the state. Hence, the state may evolve and it is threaded forward as each of the subexpressions are evaluated.

Interpreter

Our formal semantics tell us that the definitions D and environment E remain constant, but the state S may evolve along the term e being evaluated. Thus, to reflect this we update the signature of the interp function to take the state S which is also passed along to all the functions in the interp- family. We will represent the state in our implementation using a Racket hash table. The function make-hash creates an empty hash table.

Notice the Seq case, which just runs the interp function on all the sub-expressions one by one and the final value is returned. The state S is updated in-place so as long as the evalution of the subexpression happens in sequence it matches the meaning of (begin e1 e2).

;; interp :: Defn -> Env -> State -> Expr -> Val

(define (interp D E S e)

(match e

; other cases omitted

[(Seq es) (last (map (λ (e) (interp D E S e)) es))]

[(New e) (interp-new D E S e)]

[(Deref e) (interp-deref D E S e)]

[(Set! e1 e2) (interp-set! D E S e1 e2)]))

For the new case, we define interp-new, we first need a fresh location. We use the Racket provided gensym function for this. It is guaranteed to produce a fresh symbol each time it is called. The subexpression e is evaluated and it is stored in the hash (i.e., our state) with loc mapping to the value and the location is returned.

(define (interp-new D E S e)

(let ([loc (gensym)]

[v (interp D E S e)])

(begin

(hash-set! S loc v)

loc)))

To handle deref, we define interp-deref, where our interpreter evaluates the subexpression and looks up the hash for that location which is then returned.

(define (interp-deref D E S e)

(let ([loc (interp D E S e)])

(hash-ref S loc)))

Finally, to handle set!, the two subexpressions are evaluated and then the location is updated with the new value from the second subexpression.

(define (interp-set! D E S e1 e2)

(let ([loc (interp D E S e1)]

[v (interp D E S e2)])

(begin

(hash-set! S loc v)

v)))

Testing

We can convert the sample program we wrote into a test case and confirm that everything is working as expected:

(check-equal? (interp-err (parse-prog '((let ((x (new 5)))

(begin

(set! x (add1 (deref x)))

(+ 3 (deref x))))))) 9)

Aliasing, Mutability, and Freeing

TODO also add while example