Lambda: First-class Functions

Table of contents

Functions in their most general form

We added function defintions and function calls in Gross, but our languages is limited. It does not allow us to return and pass functions as arguments to programs. What we do not have, but we really should is functions as values.

Programming with functions as values is a powerful idiom that is at the heart of both functional programming and object-oriented programming, which both center around the idea that computation itself can be packaged up in a suspended form as a value and later run.

Now we’re ready to deal with functions in their most general form: λ-expressions. Let’s call this language Lambda.

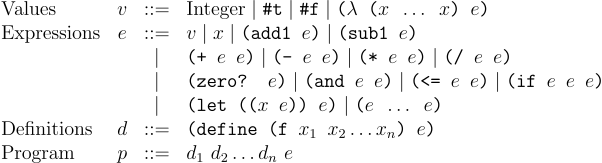

Concrete Syntax

Note: Complete implementation of the code shown in this unit can be found in the lambda implementation on GitHub.

We add λ-expressions to the syntax of expressions:

(λ (x0 ...) e)

Here x0 ... are the formal parameters of the function and e is the body.

The syntax should remind you of function definitions:

(define (f x0 ...) e)

However, you’ll notice:

- There is no function name in the λ-expression; it is an anonymous function.

- The new form is an expression — it can appear any where as a subexpression in a program, whereas definitions were restricted to be at the top-level.

There also is a syntactic relaxation on the grammar of application expressions (a.k.a. function calls). Previously, a function call consisted of a function name and some number of arguments:

(f e0 ...)

But since functions will now be considered values, we can generalize what’s allowed in the function position of the syntax for calls to be an arbitrary expression. That expression is expected to produce a function value (and this expectation gives rise to a new kind of run-time error when violated: applying a non-function to arguments), which can called with the value of the arguments.

Hence the syntax is extended to:

(e e0 ...)

In particular, the function expression can be a λ-expression, e.g.:

((λ (x) (+ x x)) 10)

But also it may be expression which produces a function, but isn’t itself a λ-expression:

(define (adder n)

(λ (x)

(+ x n)))

((adder 5) 10)

Here, (adder 5) is the function position of ((adder 5) 10). That subexpression is itself a function call expression, calling adder with the argument 5. The result of that subexpression is a function that, when applied, adds 5 to its argument.

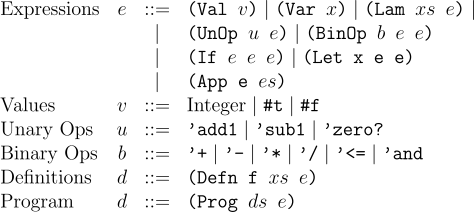

In terms of the AST, here’s how we model the extended syntax:

There are 2 new forms now: (λ (x ...) e) are the values that represent lambda functions, and we update the function application such that the function to be applied can be an expression.

Abstract Syntax

We will update the AST defintions to include the lambda terms Lam and update the application App to denote the first argument is an expression.

These definitions in our code looks like:

#lang racket

; type Values :=

; | (Val v)

; | (Lam xs e)

(struct Val (v) #:prefab)

(struct Lam (xs e) #:prefab)

; type Expr :=

; | Values

; | (Var x)

; | (UnOp u e)

; | (BinOp u e)

; | (If e e e)

; | (Let x e e)

; | (App e e)

(struct Var (x) #:prefab)

(struct UnOp (u e) #:prefab)

(struct BinOp (b e1 e2) #:prefab)

(struct If (e1 e2 e3) #:prefab)

(struct Let (x e1 e2) #:prefab)

(struct App (x args) #:prefab)

;; more defintions omitted

We update the parse function to add a match clause for lambdas and update function application:

(define (parse s)

(match s

[(? integer?) (Val s)]

[(? boolean?) (Val s)]

[(? symbol?) (Var s)]

[(list (? unop? u) e) (UnOp u (parse e))]

[(list (? binop? b) e1 e2) (BinOp b (parse e1) (parse e2))]

[`(if ,e1 ,e2 ,e3) (If (parse e1) (parse e2) (parse e3))]

[`(let ((,x ,e1)) ,e2) (Let x (parse e1) (parse e2))]

;; the next 3 lines are the new/updated cases

[`(lambda (,@xs) ,e) (Lam xs (parse e))]

[`(λ (,@xs) ,e) (Lam xs (parse e))]

[(cons e es) (App (parse e) (map parse es))]

[_ (error "Parse error!")]))

We only parse the terms that will be expressions. So we only parse the body of the lambda term (not its arguments list) and also everything in the function application.

So for example, the expression ((adder 5) 10) would be parsed as:

> (parse '((adder 5) 10))

'#s(App #s(App #s(Var adder) (#s(Val 5))) (#s(Val 10)))

> (parse '(λ (x) (+ x n)))

'#s(Lam (x) #s(BinOp + #s(Var x) #s(Var n)))

Meaning and Intepreter for Lambda functions

Let’s start by defining the behavior of the interpreter for Lambda, where the relevant forms are λs and applications.

These two parts of the interpreter must fit together: λ is the constructor for functions and application is deconstructor. An application will evaluate all its subexpressions and the value produced by e ought to be the kind of value constructed by λ. That value needs to include all the necessary information to, if given the values of the arguments es, evaluate the body of the function in an environment associating the parameter names with the arguments’ values.

So how should functions be represented? Here is a simple idea following the pattern we’ve used frequently in the interpreter:

Q: How can we represent integers?

A: With Racket integers!

Q: How can we represent booleans?

A: With Racket booleans!

So now:

Q: How can we represent functions?

A: With Racket functions!?

Great, so we will use Racket functions to represent functions in our language. Then we can implement function application with function application in Racket. This is not a coincidence—throughout this class we have been using features provided by our host language (Racket in this case) to implement features of our target language. Let’s fill in what we know so far:

;; interp :: Defn -> Env -> Expr -> Val

(define (interp D E e)

(match e

;; other cases omitted

[(Lam xs e) (interp-lam D E xs e)]

[(App e es) (interp-app D E e es)]))

;; interp-lam :: Defn -> Env -> Vars -> Expr -> Val

(define (interp-lam D E xs body)

(λ ; what are the arguments to the Racket lambda?

; what is the body of this lambda?

))

;; interp-app :: Defn -> Env -> Expr -> Exprs -> Val

(define (interp-app D E f es)

(let ([fn (interp D E f)]

[args (map (λ (arg) (interp D E arg)) es)])

(fn args)))

Starting out, it is not totally clear what parameters the representation of a function should have or what we should in the body of that function when we interpret lambdas. However, the code in the interpretation of an application sheds light on both. The first term in an application is interpreted to be a function f, followed by the rest of the terms which will be arguments to a function. Each term is interpreted individually and result is kept as a list args. So we can just use a Racket function application by applying f to the list of args.

This makes it clear that a function should potentially take any number of arguments:

;; interp-lam :: Defn -> Env -> Vars -> Expr -> Val

(define (interp-lam D E xs body)

(λ (aargs) ;; aargs is a list that will have the arguments of the function call

; what is the body of this lambda?

))

Next, what should happen when a function is applied? It should produce the answer produced by the body of the λ expression in an environment that associates xs (formal parameters) with aargs (actual parameters). Translating that to code, we get:

;; interp-lam :: Defn -> Env -> Vars -> Expr -> Val

(define (interp-lam D E xs body)

(λ (aargs)

(interp D (zip xs aargs) body)))

This also simulatenously completes our representation of function values and completes the implementation of the interpreter.

There are, however, problems.

For one, this approach does not model how λ-expressions are able to capture the environment in which they are evaluated. Consider:

(let ((y 8))

(λ (x) (+ x y)))

This evaluates to a function that, when applied, should add 8 to its argument. It does so by evaluating the body of the λ, but in an environment that both associates x with the value of the argument, but also associates y with 8. That association comes from the environment in place when the λ-expression is evaluated. The interpreter as written will consider y is unbound!

The solution is easy: in order for (Lambda, our target language) functions to capture their (implicit) environment, we should capture the (explicit) environment in the (Racket, our host language) function:

;; interp-lam :: Defn -> Env -> Vars -> Expr -> Val

(define (interp-lam D E xs body)

(λ (aargs)

(interp D (append (zip xs aargs) E) body)))

We have a final issue to deal with. What should we do about references to functions defined at the top-level of the program? In other words, how do we make function applicaton when the function was defined with define?

One possible answer to re-use our new power of λ-expression by considering define-bound names as just regular old variables, but changing the way that variables are interpreted so that when evaluating a variable that is not bound in the local environment, we consult the program definitions and construct the function value at that moment.

;; interp :: Defn -> Env -> Expr -> Val

(define (interp D E e)

(match e

;; other cases omitted

[(Lam xs e) (interp-lam D E xs e)]

[(Defn x xs e) (interp-lam D '() xs e)]

[(App e es) (interp-app D E e es)]))

;; lookup :: Defn -> Env -> Symbol -> Val

(define (lookup D E x)

; lookup the environment first, then the list of definitions

(match E

['() (lookup-defn D E D x)]

[(cons (list y val) rest) (if (eq? x y) val

(lookup D rest x))]))

;; lookup-defn :: Defn -> Defn -> Symbol -> Val

(define (lookup-defn D E defns x)

(match defns

['() (raise (Err (string-append "Unbound identifier: " (symbol->string x))))]

[(cons (Defn f xs body) rest) (if (eq? f x)

(interp D E (Defn f xs body))

(lookup-defn D E rest x))]))

The lookup function is modified such that after looking up the environment, if it does not find a binding it looks up the list of definitions using lookup-defn. There is an additional case in our interp function that uses interp-lam to evaluate the definitions. It, however, passes an empty environment '() for definitions as defined functions are top-level and does not capture the environment unlike lambdas.

The complete implementation can be found in interp.rkt on Github. We did not give the complete formal semantics for evaluation of Lambda, but we will cover it in the next module.

We can see our interpreter to run an example program:

> (interp-err (parse-prog '((let ([adder (λ (x) (λ (y) (+ x y)))])

(let ([adder2 (adder 2)])

(adder2 4))))))

6

Testing

We can add a few tests to check if our interpreter is behaving correctly:

(check-equal? (interp-err (parse-prog '((let ((foo (λ (x) (+ x 42))))

(foo 3))))) 45)

(check-equal? (interp-err (parse-prog '((define (foo x)

(- x x))

(let ((foo (λ (x) (+ x 42))))

(foo 3))))) 45)

(check-equal? (interp-err (parse-prog '((define (bar x)

(- x x))

(let ((foo (λ (x) (+ x 42))))

(bar 3))))) 0)

(check-equal? (interp-err (parse-prog '((define foo 42)

(+ foo 3)))) 45)

(check-equal? (interp-err (parse-prog '(((lambda (x) (add1 x)) 4)))) 5)

(check-equal? (interp-err (parse-prog '((let ([adder (λ (x) (λ (y) (+ x y)))])

((adder 3) 4))))) 7)

(check-equal? (interp-err (parse-prog '((let ([adder (λ (x) (λ (y) (+ x y)))])

(let ([adder2 (adder 2)])

(adder2 4)))))) 6)

Discussion

We should take a pause, and appreciate the milestone we have reached. Our Lambda language implements an elaborate version of the Lambda Calculus—a general purpose programming language. Thus, the language Lambda can represent all possible computation one can ever represent in any general purpose language (including C, C++, Java, Ruby, Python, JavaScript, Haskell). We will take a look at this aspect in the next module.