Gross: Function Definitions and Calls

Table of contents

Functions

Let us start turning the previous language, Fraud, into a real programming language. Let us say you write an expression to compute a particular value. Writing an expression for that will only work for the single computation you have written down. For example, if you want to compute a factorial of 5, you will have to write a program (* 5 (* 4 (*(* 5 (* 4 (* 3 (* 2 1)))) that will compute the result as 120. If you want to find the factorial of any number, you will have to write down infinite number of expressions in Fraud. This means the expressiveness of our language is still severely restricted.

The solution is to bring in the computational analog of inductive data. Just like we can describe our programs by inductively composing the structs we defined, our language needs to be able to define arbitrarily long running computations. Crucially, these arbitrarily long running computations need to be described by finite sized programs. The analog of inductive data are recursive functions.

So let’s now remove this limitation by incorporating functions, and in particular, recursive functions, which will allow us to compute over arbitrarily large data with finite-sized programs. We will call this language Gross.

Concrete Syntax

Note: Complete implementation of the code shown in this unit can be found in the gross implementation on GitHub.

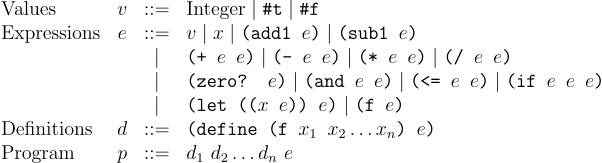

We will extend the syntax by introducing a new syntactic category of programs, which consist of a sequence of function definitions followed by an expression:

(define (f0 x00 ...) e0)

(define (f1 x10 ...) e1)

...

e

And the syntax of expressions will be extended to include function calls:

(fi e0 ...)

where fi is one of the function names defined in the program.

Note that functions can have any number of parameters and, symmetrically, calls can have any number of arguments. A program consists of zero or more function definitions followed by an expression.

An example concrete Gross program is:

(define (fact n)

(if (zero? n) 1

(* n (fact (sub1 n)))))

(fact 5)

Thus the complete grammar for Gross looks like below. Note how we have added definitions, and function application to expressions, and programs represent a sequence of defintions followed by an expression.

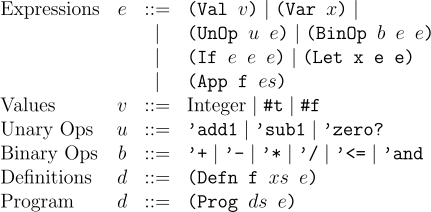

Abstract Syntax

We will define new structs for the AST corresponding to the new additions we made to the concrete syntax. The grammar for the AST nodes look like:

Defining the new structs, our AST definition looks like:

#lang racket

(provide Val Var UnOp BinOp If Let App Defn Prog Err Err?)

;; type Expr =

;; | (Val v)

;; | (Var x)

;; | (UnOp u e)

;; | (BinOp b e e)

;; | (If e e e)

;; | (Let x e e)

;; | (App f es)

(struct Val (v) #:prefab)

(struct Var (x) #:prefab)

(struct UnOp (u e) #:prefab)

(struct BinOp (b e1 e2) #:prefab)

(struct If (e1 e2 e3) #:prefab)

(struct Let (x e1 e2) #:prefab)

(struct App (f args) #:prefab)

;; type Definition =

;; | (Defn f xs e)

(struct Defn (f args e) #:prefab)

;; type Prog =

;; | (Prog ds e)

(struct Prog (defns e) #:prefab)

(struct Err (err) #:prefab)

If you notice carefully, you will see our programs are not just s-expression any more. It is a sequence of s-expressions that need to parsed into the AST. All but the last should be a definition, with the final one being an expression like all previous languages. So we will have to change our parser accordingly.

We update the parse function to add a match clause for function application, where the first item is matched to be a symbol, i.e., the name of the function, followed by the list of all arguments that are parsed to make the App struct.

;; S-Expr -> Expr

(define (parse s)

(match s

[(? integer?) (Val s)]

[(? boolean?) (Val s)]

[(? symbol?) (Var s)]

[(list (? unop? u) e) (UnOp u (parse e))]

[(list (? binop? b) e1 e2) (BinOp b (parse e1) (parse e2))]

[`(if ,e1 ,e2 ,e3) (If (parse e1) (parse e2) (parse e3))]

[`(let ((,x ,e1)) ,e2) (Let x (parse e1) (parse e2))]

[`(,(? symbol? f) ,@args) (App f (map parse args))]

[_ (error "Parse error!")]))

Now, to parse function definitions, we define a new function parse-defn that given an s-expression, matches against a (define ( start, followed by the name of the function and the list of names of arguments, followed by the body of the function defintion. These are used to create the final Defn struct.

;; S-Expr -> Defn

(define (parse-defn s)

(match s

[`(define (,(? symbol? f) ,@args) ,e) (Defn f args (parse e))]

[_ (error "Parse error!")]))

Finally, we define a parse-prog function to put these two pieces together to parse it into a full program. Remember, parse-prog now has to deal with a list of s-expressions:

;; List S-Expr -> Prog

(define (parse-prog s)

(match s

[(cons e '()) (Prog '() (parse e))]

[(cons defn rest) (match (parse-prog rest)

[(Prog d e) (Prog (cons (parse-defn defn) d) e)])]))

The parse-prog function has two cases. First, is the base case where there are no definitions, so the final expression is parsed with the definitions list empty. Second, recursively parse the definitions, and build the Prog AST node from intermediate results.

Let us try parsing the factorial function through our new parser:

> (parse-prog '((define (fact n)

(if (zero? n) 1

(* n (fact (sub1 n)))))

(fact 5)))

'#s(Prog (#s(Defn fact (n) #s(If #s(UnOp zero? #s(Var n)) #s(Val 1) #s(BinOp * #s(Var n) #s(App fact (#s(UnOp sub1 #s(Var n)))))))) #s(App fact (#s(Val 5))))

Meaning of Functions

With parsing handled, we can now start giving meaning to Gross programs:

- The meaning of

(define (f x0 ... xn) e)is the definition of a functionfthat takes argumentsx0throughxnand executes its bodye. The act of defining the function does not produce any result. - The meaning of

(f e0 ... en)is application of an already defined functionf, with argumentse0throughen.

Before we go further, let’s establish a few definitions. It will help us understand what we mean by function application. In the definition of (fact n) we refer to n as a formal parameter. When we apply fact to an expression as in (fact 5) we refer to 5 as an actual parameter or an argument. We refer to the function applied to an expression such as (fact 5) as an application of fact. Finally, we refer to the expression that defines fact, (if (zero? ...) ...) as the body of fact and the scope of n as the body of fact.

Given all these nice definitions we can describe the application of fact to any actual parameter as substituting its formal parameter, n, with the actual parameter from the body of fact. We can be a just little more formal and general. The application of any function to an actual parameter is the substitution of its formal parameter with its actual parameter in its body. Looking back to (fact 5) in light of this definition, applying fact to 5 is substituting n with 5 in (if (zero? n) 1 (* n (fact (sub1 n)))).

We can rephrase the above in terms of using an environment. The application of fact to any actual parameter as creating a new environment with its formal parameter, n bound tothe actual parameter in the body of fact. The application of any function to an actual parameter is the binding of its formal parameter with its actual parameter in a fresh environment of its body. Looking back to (fact 5) in light of this definition, applying fact to 5 is binding n to 5 in an environment for (if (zero? n) 1 (* n (fact (sub1 n)))).

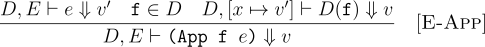

Formally stated, this looks as below. Notice, this time on the left of ⊢ we have D and E, denoting the list of definitions and the environment respectively.

The rule states to apply a function, we have to evaluate the arguments, check if the function we are calling is in the set of defined functions, and then create the new environment and evaluate the body of the defined function.

Interpreter

As we have both definitions D and the environment E on the left of the ⊢, the interp function also accepts these two things in addition to the expression it is evaluating. We add a case for function application App. The interp-app function implements the E-App rule above. It looks up the function in the list of the definitions, followed by evaluating all the arguments in the given environment. Once done, it makes a new environment with the formal and actual parameters bound together and executes the body of the function.

;; interp :: Defns -> Env -> Expr -> Val

(define (interp defn env e)

(match e

[(Val v) v]

[(Var x) (lookup env x)]

[(UnOp u e) (interp-unop defn env u e)]

[(BinOp b e1 e2) (interp-binop defn env b e1 e2)]

[(If e1 e2 e3) (interp-if defn env e1 e2 e3)]

[(Let x e1 e2) (interp defn

(store env x (interp defn env e1))

e2)]

[(App f actual) (interp-app defn env f actual)]))

(define (interp-app defn env f actual-args)

(match (lookup-defn f defn) ; lookup the function defintions

[(cons formal-args body) (let ((interped-args (map (λ (arg)

(interp defn env arg))

actual-args)))

(interp defn (zip formal-args interped-args) body))]))

The lookup-defn function is similar to the lookup function we wrote for the environment in Fraud. It traverses the list of definitions and if the name matches returns the pair of actual parameters and body of the function.

;; lookup-defn :: Symbol -> Listof Defn -> (Symbols, Expr)

(define (lookup-defn f defns)

(match defns

['() (raise (Err (string-append "Definition not found: " (symbol->string f))))]

[(cons d rest) (match d

[(Defn name args body) (if (eq? name f)

(cons args body)

(lookup-defn f rest))])]))

Finally, as our programs are not just expressions, but represented by the Prog struct, we write a function a function to interpret Prog called interp-prog. It calls the interp function with the list of definitions and an empty environment. We also update the interp-err (the error handling wrapper function) to now call the interp-prog function.

;; interp-prog :: Prog -> Val

(define (interp-prog prog)

(match prog

; '() is the empty environment

[(Prog defns e) (interp defns '() e)]))

;; interp-err :: Expr -> Val or Err

(define (interp-err e)

(with-handlers ([Err? (λ (err) err)])

(interp-prog e)))

With that we can run the example of factorial function through our implementation of Gross:

> (interp-err (parse-prog '((define (fact n)

(if (zero? n) 1

(* n (fact (sub1 n)))))

(fact 5))))

120

Testing

We can convert the above factorial function to a test case:

(check-equal? (interp-err (parse-prog '((define (fact n)

(if (zero? n) 1

(* n (fact (sub1 n)))))

(fact 5)))) 120)

We can add a test for a mutually recursive function that tests if a given argument is odd or even:

(check-equal? (interp-err (parse-prog '((define (odd? x)

(if (zero? x) #f

(even? (sub1 x))))

(define (even? x)

(if (zero? x) #t

(odd? (sub1 x))))

(odd? 45)))) #t)

Discussion

A couple of things to note:

- since the function definition environment is passed along even when interpreting the body of function definitions, this interpretation supports recursion, and even mutual recursion.

- functions are not values (yet). We cannot bind a variable to a function. We cannot make a list of functions. We cannot compute a function. The first position of a function call is a function name, not an arbitrary expression. Nevertheless, we have significantly increased the expressivity of our language.