Fraud: Local bindings and variables

Table of contents

Bindings and variables

Now, let us add local bindings to our language. This will allow us to declare a variable, bind a value to it, and use the variable in expressions.

(let ((id0 e0)) e1)

This form is called a let binding, that binds the identifier id0 to the value of e0 within the scope of the expression e1.

This is a simplification of Racket’s let binding form, that allows binding of multiple variables:

(let ([id0 e0]

[id1 e1]

...

[idn en]) em)

that allows you to declare multiple identifiers id0 through id1, binding them to values of expressions e0 through e1 respectively in the scope of the expression em.

An example program written using let bindings will look like:

(let ((x (add1 6)))

(let ((y (+ 6 x)))

(+ x y)))

This program binds the value of (add1 6) to x and sum of 6 and x to y and then calculates their sum, evaluating to 20.

We will extend our previous language Defend to add let bindings, and call this new language Fraud.

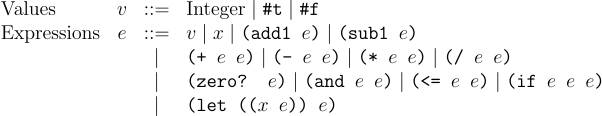

Concrete Syntax

We extend the concrete syntax of Defend with a few forms to support bindings. First, we add x to the language, which denotes any identifier, i.e., any string that can be represented as a symbol in Racket (alpha-numeric, and symbols like -, +, =, <, >, and similar). These can denote the name of any variable of declarations in our language - Fraud. Second, we add a (let ((x e)) e) form to the language. This allows us to declare a new variable x and bind the first expression e to it, and this x is only bound locally in the second expression e.

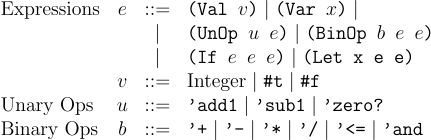

Abstract Syntax

With the surface syntax of the language defined, we can now turn to define the AST. Because we have two new kinds of expressions in the language that do not fit in the other AST nodes, we will define two new AST nodes. First, (Var x) for representing variables in the AST. Second, we have (Let x e e) for representing let.

The code for the AST is straightforward:

#lang racket

(provide Val UnOp BinOp If Err Err? Let Var)

;; type Expr =

;; | other expression forms omitted for brevity

;; | (Var x)

;; | (Let x e e)

; full set of struct definitions can be found in ast.rkt

(struct Var (x) #:prefab)

(struct Let (x e1 e2) #:prefab)

The parser is slightly longer than Con, but almost similar:

#lang racket

(require "ast.rkt")

(provide parse)

;; full parser can be found in parser.rkt

;; S-Expr -> Expr

(define (parse s)

(match s

; ... rest of the cases omitted for brevity

[(? symbol?) (Var s)]

[`(let ((,x ,e1)) ,e2) (Let x (parse e1) (parse e2))]

[_ (error "Parse error!")]))

In the two new cases, the first one matches against a symbol in the concrete syntax, and if so creates a new Var struct. Recall that programs are s-expressions, which are lists. So a program in concrete syntax is written as a list is '(+ x 5), which in equivalent to (list '+ 'x 5). The parser when it comes across the '+ symbol will produce the BinOp node, which will recursively call parse on the following two subexpressions. Then 'x will be parsed as a symbol and represented as a Var node with new match clause we just added. The second clause for let, matches with the form (let (( literally, and then matches with the variable as x followed by the binding expression e1 followed by e2 where the identifier is bound.

This is how the AST looks when parsed:

> (parse '(let ((x 42)) (add1 x)))

'#s(Let x #s(Val 42) #s(UnOp add1 #s(Var x)))

Substitution

We are done with the syntactic part of extending the language and now move on to defining its semantics:

- the meaning of a let expression

(let ((x e0)) e)is the meaning ofe(the body of thelet) whenxmeans the value ofe0(the right hand side of thelet), - the meaning of a variable

xdepends on the context in which it is bound. It means the value of the right-hand side of the nearest enclosingletexpression that bindsx. If there is no such enclosing let expression, the variable is meaningless.

Let us understand these rules with a few examples:

x: this expression is meaningless on its own.(let ((x 7)) x): this means7, since the body expression,x, means7because the nearest enclosing binding forxis to7, which means7.(let ((x 7)) 2): this means2since the body expression,2, means2.(let ((x 7)) (add1 x)): this means8since the body expression,(add1 x), means one more thanxandxmeans7because the nearest enclosing binding forxis to7.(let ((x (add1 7))) x): this means8since the body expression,x, means8because the nearest enclosing binding forxis to(add1 7)which means8.(let ((x 7)) (let ((y 2)) x)): this means7since the body expression,(let ((y 2)) x), means2since the body expression,x, means7since the nearest enclosing binding forxis to7.(let ((x 7)) (let ((x 2)) x)): this means2since the body expression,(let ((x 2)) x), means2since the body expression,x, means2since the nearest enclosing binding forxis to2.(let ((x (add1 x))) x): this is meaningless, since the right-hand side expression,(add1 x)is meaningless because x has no enclosing let that binds it.(let ((x 7)) (let ((x (add1 x))) x)): this means8because the body expression(let ((x (add1 x))) x)means8because the body expression,x, is bound to(add1 x)is in the nearest enclosingletexpression that bindsxand(add1 x)means8because it is one more thanxwherexis bound to7in the nearest enclosingletthat binds it.

Make sure you have a good understanding of how binding works in these examples before moving on. Remember: you can always check your understanding by pasting expressions into Racket and seeing what it produces, or better yet, write examples in DrRacket and hover over identifiers to see arrows between variable bindings and their occurrences.

One thing that should be clear from these examples is that the meaning of a sub-expression is not determined by the form of that expression alone. For example, x could mean 7, or it could mean 8, or it could be meaningless, or it could mean 22, etc. It depends on the context in which it occurs. So in formulating the meaning of an expression, this context must be taken into account.

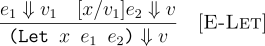

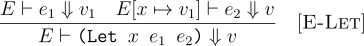

A good analogy where context matters for the meaning of an expression is algebra, where it is common to write expressions as given x = 7 + 3, find the value of expressions like 2x + 7. In such cases, you would first find the value of x to be 10 and substitute into the given expression to find it is 27. Turns out, we can given meaning to let expression in a similar manner as shown in the E-Let rule:

The above rule states, to give meaning to a let expression, we first need to give meaning to the binding expressions e1 as v1, then all we need to do is substitute all occurences of the variable x in body of the let expression. We are using the [x/v1]e2 notation to denote substitute all occurences of x with v1 in e2. Then all we have to do is define how substitution behaves. It was simple for algebra, but for programming language it is more involved.

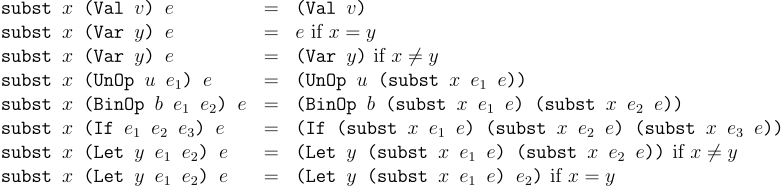

Let us define substition as a function subst that takes what variable it is substituting, with the value it is substituting, and in the expression it is substituting. It computes a new version of the in expression where all occurences of what has been substituted by with:

The subst function keeps values as-is, as there is nothing to substitute. All the other cases, it does what we expect, recursively applies subst to all subexpressions to replace all occurences. Only two cases are interesting, the ones for Var and Let. For the Var case, we only substitute a variable if it has the same name as the one we are subtituting. For Let, if a let binding is redefining the same variable with a new expression, we only substitute it in the binding expression. We do not substitute in the body of the let, as it should be substituted with the new redefined value, when we give meaning to the redefining let. Conversely, if the let binding is for any other variable, it does not matter and we can substitute in both the binding expression and the body of the let.

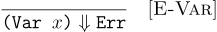

Note, that we did not give any meaning to variables x yet. Look at the Var case for subst, and you will notice all occurences of a bound variables will be substituted with their values as we give meaning to an expression. That will leave us only with programs, where we have unbound variables or free variables. For example, (add1 x) or (let ((x 5)) y) where x and y are free variables respectively. Such free variables result in an error.

Interpreter via substitution

Note: Complete implementation of the code shown in this section can be found on the fraud-subst implementation on GitHub.

With the formal semantics defined, we can translate that to our interpreter code trivially. First let us translate the subst definition to a program:

;; subst :: Symbol -> Expr -> Expr -> Expr

(define (subst what with in)

(match in

[(Val v) (Val v)]

[(Var x) (if (eq? x what)

with

(Var x))]

[(UnOp u e) (UnOp u (subst what with e))]

[(BinOp b e1 e2) (BinOp b (subst what with e1)

(subst what with e2))]

[(If e0 e1 e2) (If (subst what with e0)

(subst what with e1)

(subst what with e2))]

[(Let x e1 e2) (if (eq? x what)

(Let x (subst what with e1) e2)

(Let x (subst what with e1) (subst what with e2)))]))

Then we have to add new cases to the interpreter to reflect the above inference rules using subst:

;; interp :: Expr -> Val

(define (interp e)

(match e

[(Val v) v]

[(Var x) (raise (Err "Unbound identifier"))]

[(UnOp u e) (interp-unop u e)]

[(BinOp b e1 e2) (interp-binop b e1 e2)]

[(If e1 e2 e3) (interp-if e1 e2 e3)]

[(Let x e1 e2) (interp (subst x (Val (interp e1)) e2))]))

The above interpreter only has two new cases for Var and Let directly reflecting the rules with  relation. We can try running this on a few examples:

relation. We can try running this on a few examples:

> (interp-err (parse '(let ((x 7)) x)))

7

> (interp-err (parse '(let ((x 7)) (let ((x (add1 x))) x))))

8

> (interp-err (parse '(let ((x 7)) y)))

'#s(Err "Unbound identifier")

Thus we have a working implementation of let and variables. When the interpreter sees an identifier, you might have had a sense that it needs to “look it up”. Not only did this interpreter not look up anything, we defined its behavior on variables to be an error! While absolutely correct, this is also a little surprising. More importantly, we write interpreters to understand and explain languages, and this implementation might strike you as not doing that, because it doesn’t match our intuition.

There’s another problem with substitution, which is the number of times it has traverse the source program AST. It would be nice to have to traverse only those parts of the program that are actually evaluated and only when necessary. But substitution traverses everything, like unvisited branches of conditionals, and forces the program to be traversed once for substitution and once again for interpretation.

Environments

Let us follow our intuition about looking up variables. To look up variables for values, we would need to store them in some directory. We can create a map from variables to their values, which we call the environment. This fits our mental model: when we declare variables we store them in the environment and when we evaluate variables we look up their values the environment. This also addresses our second concern about traversing the source program too many times. Storing a variable in the environment merely denotes our intent to substitute the identifier later on. Only when we evaluate a variable do we substitute it by looking up in the environment. In practice, all commonly used languages use the environment in their implementation.

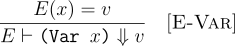

We will denote the environment as E. Storing a variable in the environment is denoted as  , while lookup of a variable

, while lookup of a variable x is denoted as  . With our environment defined, we can now redefine the meaning of

. With our environment defined, we can now redefine the meaning of let in terms of the environment:

The E ⊢ is now a part of all rules in our language. The ⊢ symbol is called the turnstile. In this context, you can read this as “Given an environment E, (Let x e1 e2) means v if e1 means v1 in the same enviroment E and e2 means v under a new environment same as E with x mapped to v1”. Now the rule for let matches our intuition of storing a value to a variable.

Similarly, the rule for interpreting a variable would be:

This rule is read in a similar fashion: given an environment E, the meaning of (Var x) is the value of looking up x in the environment E.

Note, how we did not define a new programming language for this change. We did not need to define a new concrete syntax, abstract syntax or the parser. All we are changing is the implementation strategy. We can now write an interpreter that uses environments.

Interpreter with environments

Note: Complete implementation of the code shown in this section can be found on the fraud implementation on GitHub.

We will use Racket’s lists to define our environment. One could use Racket’s hash tables to implement environments as well.

For our implementation, an empty enviroment is '(). Storing a variable to a value stores a list in the environment. So an environment containing x = 2 will be denoted as '((x 2)). Storing y = 5 in the same environment, will result in a new environment '((y 5) (x 2)). The same variables can be redefined as well. If we re-bind x = 42 in the environment, it will be stored as '((x 42) (y 5) (x 2)). We define a function store to define this operation:

;; store :: Env -> Symbol -> Val -> Env

(define (store env x val)

(cons (list x val) env))

Similarly, our look up operation on the environment will walk the list and return the first occurence of the identifier. If it is not found it will raise an error:

;; lookup :: Env -> Symbol -> Val

(define (lookup env x)

(match env

['() (raise (Err "Unbound identifier"))]

[(cons (list y val) rest) (if (eq? x y) val

(lookup rest x))]))

Just like we did for substitution, we have to define two new cases in the interpreter for the Var and the Let case. Note, just like how our inference rules were updated when we defined the meaning of the language to include an environment, our interp and similar functions are also updated to include env as a parameter denoting the environment. For (Var x), all we do is call lookup. For (Let x e1 e2), we interpret the body e2, after we interpret the binding expression e1 in the provided environment and store the result in the new environment.

;; interp :: Env -> Expr -> Val

(define (interp env e)

(match e

[(Val v) v]

[(Var x) (lookup env x)]

[(UnOp u e) (interp-unop env u e)]

[(BinOp b e1 e2) (interp-binop env b e1 e2)]

[(If e1 e2 e3) (interp-if env e1 e2 e3)]

[(Let x e1 e2) (interp

(store env x ; env will be updated

(interp env e1)) ; after e1 is evaled in old env

e2)])) ; e2 evaluated in updated env

We can try running this on the same set of examples:

> (interp-err (parse '(let ((x 7)) x)))

7

> (interp-err (parse '(let ((x 7)) (let ((x (add1 x))) x))))

8

> (interp-err (parse '(let ((x 7)) y)))

'#s(Err "Unbound identifier")

If substitutions and environments result in the same thing, why did we take the long winded way to learn both? Substitutions take an expression-centric view on bindings, i.e., all operations are done at the expression level. Environment, on the other hand, take an abstract machine view of bindings: there is some environment in your machine that you can store or do lookup in while interpreting you program. Having two ways to realize the same thing is great as we can cross-check our implementation against both to see if they agree. If they do not at least one of them is wrong. We can also prove that both approaches will give the same result for all possible programs in our language, but that is out of scope for this class.

Definitions

Some definitions related to terms used in this article:

- Instance: Any usage of an identifier

- Binding instance: The instance of an identifier where it is defined and given a value

- Scope: The code region where an identifier bound

- Bound instance: An instance of an identifier occurring the scope of a binding instance for that identifier

- Free: An instance of an identifier occurring outside the scope of a binding instance for that identifier

- Substitution: Replacing an identifier by its value

- Environment: A map of bindings

- Binding: An identifier/value pair added to an environment when evaluating a binding instance

Testing

We can write a few cases for both the interpreters to see if they behave as we would expect:

(check-equal? (interp-err (parse '(let ((x 1)) (+ x 3)))) 4)

(check-equal? (interp-err (parse '(let ((x 1))

(let ((y 2))

(+ x y))))) 3)

(check-equal? (interp-err (parse '(let ((x (add1 6)))

(let ((x (+ 6 x)))

(/ x 2))))) 6)

(check-equal? (interp-err (parse '(let ((x (add1 6)))

(let ((x (+ 6 x)))

(/ x y)))))

(Err "Unbound identifier")))

We can extend this to check if both our substitution and environment-based interpreter agree for a set of programs.