Defend: Handling errors

Table of contents

A crashing language

We have seen that Con fails for programs that attempt to use boolean values where numbers should be used or numbers where boolean values should be used. Before addressing this problem in Con, let’s look at how errors should be handled generally.

We defined a new language called Con using Racket to build the parser and interpreter. We will refer to Con as the source language. We refer to Racket as the host language or implementation language. The distinction is we are building tools for the language Con, but using Racket to build them.

When the current Con interpreter fails, it fails in the host language. When we call the Racket error function (in parser.rkt) we jump out of our interpreter and generate a Racket error message. Further, if we try running programs that use numbers and booleans at incorrect places, we raise a Racket error message.

As an example, here is a simple program in our Con interpreter:

> (interp (parse '(add1 #t)))

add1: contract violation

expected: number?

given: #t

The contract violation exception comes from Racket. Our language does not have contracts! However, things could have been worse. Here at least our interpreter crashes, but there could be scenarios where our interpreter computes a wrong value. This approach of failing in our host language (Racket) works, but we cannot control errors and our only choice is hard failure. If errors happen, our control of execution ends and the interpreter crashes. Java uses an innovative approach where exceptions are Java data structures that allow us to write Java programs to process them. This is how systems like Eclipse can allow new tools that generate error messages to simply be plugged into the infrastructure. Right now, we can’t do this.

Our only choice is to fail completely. What if our interpreters can avoid failures? What if we can predict failures during execution? This results in systems that are more robust and code that we can better control. For now, we will design a language called Defend that will handle errors dynamically or at run-time. Our interpreter will generate error messages as data structures that we can process how we choose.

Modeling Errors

Before our language can handle errors, we have to create a value that represents errors. An error can convey a variety of information such as:

- The type of error. For example: Java has

ArrayIndexOutOfBoundsExceptionorNullPointerException, Python hasRuntimeErrororTypeError - The error message. This is typically represented as a string.

- Some other fields depending on the error message such as expected value vs. the provided value that caused the error. These can help provide better error messages such as a value of type string was provided when an integer was expected.

This can be represented as the following definition in Racket:

(struct Err (errtype errmsg expected received) #:prefab)

While showing useful error messages are interesting in their own right, for this class we will use a simple definition of Err that only has the error message (errmsg). This will be enough to demonstrate how to design language that can handle errors. We can now add this to the definition in ast.rkt:

#lang racket

(provide Val UnOp BinOp If Err Err?)

;; type Expr =

;; | (Val v)

;; | (UnOp u e)

;; | (BinOp b e e)

;; | (If e e e)

(struct Val (v) #:prefab)

(struct UnOp (u e) #:prefab)

(struct BinOp (b e1 e2) #:prefab)

(struct If (e1 e2 e3) #:prefab)

(struct Err (err) #:prefab)

Note, how we are exporting two definitions for the newly declared struct. (Err ...) constructs an Err struct while (Err? x) checks if the provided x is an Err struct.

We also did not update our comment about the Expr type. This means our source language is still same and the values our programs produce are also same. The Err struct will signal an error when the execution of our program runs into problems, however, our language still does not have first class errors. In other words, there is no way to create Err values or handle them in our language (yet!). So we do not have update anything in our concrete or abstract syntax.

Meaning of Defend

Our language, Defend, produces the same results as Con when the programs are defined in the relation. Earlier programs not defined in the  relation would crash with errors from the Racket runtime. So to give meaning to programs in Defend, we have to have the same rules as Con, but with additional rules for situations which lead to errors.

relation would crash with errors from the Racket runtime. So to give meaning to programs in Defend, we have to have the same rules as Con, but with additional rules for situations which lead to errors.

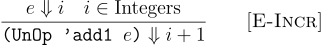

Let us do this with the add1 operation in our language:

This rule is the same as the one we wrote for our Arithmetic language, except for one thing. We now explicitly state in the premise that the add1 operation has a valid meaning only if e evaluates to some i that is an integer. Our previous languages never explicitly stated this—which means we delegated the i + 1 to mean the increment which eventually crashed in Racket.

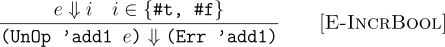

In E-IncrBool we state that for other values in our language (only booleans in this case) the language fails and the error contains some information as to where the error happened. In this case we are just storing that the error happened in the add1 function.

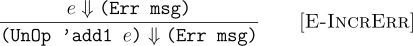

This, however, is not enough. The term e (subexpression of add1) can also mean an error in Defend. In such a case, the correct behavior would be propagate that error in the meaning of (add1 e) expression.

As these rules above show, writing down the operational semantics that handle error for even a simple operation in our language (add1) blew up the number of inference rules to 3 from 1. This will be more complicated if any operation in our language depends on more subexpressions that can lead to errors. Formalizing errors for that is a lot of work, and it also distracts us from the interesting semantics of the language.

Interpreter for Defend

We can translate the rules in a similar fashion for writing an interpreter for Defend. But handling all the cases turns out to be tedious, and we can make use of Racket’s exception handling mechanism to simplify things for use during error propagation.

Let us first look at the case for handling the error semantics for add1:

(define (interp-unop u e)

(match u

['add1 (match (interp e)

[(? integer? i) (add1 i)]

[_ (raise (Err "add1 expects int"))])]

...))

Here we translated the first two rules we had written above into the above two cases. The first case checks if the subexpression e is an integer and only then applies Racket’s add1 thus guaranteed to not fail. For values of any other type, add1 should fail with an error.

Note, we do not return the Err value we construct here, instead we raise it as an exception. When we raise an exception, the value is automatically passed down the call stack until it has the appropriate error handler. So we can now add an error handler:

(define (interp-err e)

(with-handlers ([Err? (λ (err) err)])

(interp e)))

We define a new function interp-err, which has the same behaviour as our interp, except it now handles errors raised by our language correctly. All interp-err does is wrap the call to the original interp function with a with-handlers call. The with-handlers function takes two arguments, the first argument registers the exception handlers, and the second where we provide the expression whose exceptions should be handled. The exception handler we register is only for Err values: any errors from our language will be handled by this handler as our interpreter only produces Err values when there is an error. If there are any other errors (like errors originating from badly written interpreter, or the Racket runtime) it will still show up as expected. Our handler checks if the exception is an Err value using the Err? predicate and then it just returns the error as-is.

Why did we implement our interpreter this way? Look at the behavior of the  relation for

relation for add1, and we can see any subexpression that raises an error should be passed along and no further computation should take place. The error handling mechanism in Racket provides us exactly that—once we raise an exception it bubbles up until the error handler is reached. We did not have to do a case-by-case analysis for the entire interpreter!

With that we can add similar error guards for the entire language:

;; interp-err :: Expr -> Val or Err

(define (interp-err e)

(with-handlers ([Err? (λ (err) err)])

(interp e)))

;; interp :: Expr -> Val

(define (interp e)

(match e

[(Val v) v]

[(UnOp u e) (interp-unop u e)]

[(BinOp b e1 e2) (interp-binop b e1 e2)]

[(If e1 e2 e3) (interp-if e1 e2 e3)]))

;; interp-unop :: UnOp -> Val

(define (interp-unop u e)

(match u

['add1 (match (interp e)

[(? integer? i) (add1 i)]

[_ (raise (Err "add1 expects int"))])]

['sub1 (match (interp e)

[(? integer? i) (sub1 i)]

[_ (raise (Err "sub1 expects int"))])]

['zero? (match (interp e)

[0 #t]

[_ #f])]))

;; interp-binop :: BinOp -> Val

(define (interp-binop b e1 e2)

(match b

['+ (match* ((interp e1) (interp e2))

[((? integer? i1) (? integer? i2)) (+ i1 i2)]

[(_ _) (raise (Err "+ requires int"))])]

['- (match* ((interp e1) (interp e2))

[((? integer? i1) (? integer? i2)) (- i1 i2)]

[(_ _) (raise (Err "- requires int"))])]

['* (match* ((interp e1) (interp e2))

[((? integer? i1) (? integer? i2)) (* i1 i2)]

[(_ _) (raise (Err "* requires int"))])]

['/ (match* ((interp e1) (interp e2))

[((? integer? i1) (? integer? i2)) (if (eq? i2 0)

(raise (Err "division by 0 not allowed"))

(quotient i1 i2))]

[(_ _) (raise (Err "/ requires int"))])]

['<= (match* ((interp e1) (interp e2))

[((? integer? i1) (? integer? i2)) (<= i1 i2)]

[(_ _) (raise (Err "<= requires int"))])]

['and (match (interp e1)

[#f #f]

[? (interp e2)])]))

;; interp-if :: If -> Val

(define (interp-if e1 e2 e3)

(match (interp e1)

[#f (interp e3)]

[_ (interp e2)]))

Notice the case for the / operation. The way we have defined error handling in our language not only protects us against type errors in the language, but also any other errors that may happen. A number divided by 0 is an undefined operation and now we can check and raise such an error gracefully without crashing via the Racket runtime.

Running our interpreter this time:

> (interp-err (parse '(add1 #t)))

'#s(Err "add1 expects int")

> (interp-err (parse '(add1 (+ 5 #f))))

'#s(Err "+ requires int")

> (interp-err (parse '(/ 5 (sub1 1))))

'#s(Err "division by 0 not allowed")

Correctness

We can turn the above examples to automatic tests:

(module+ test

(check-eqv? (interp-err (parse '(+ 42 (sub1 34)))) 75)

(check-eqv? (interp-err (parse '(zero? (- 5 (sub1 6))))) #t)

(check-eqv? (interp-err (parse '(if (zero? 0) (add1 5) (sub1 5)))) 6)

(check-pred Err? (interp-err (parse '(add1 (+ 3 #f)))))

(check-pred Err? (interp-err (parse '(add1 (and #t #t)))))

(check-pred Err? (interp-err (parse '(/ 5 (sub1 1))))))

As we can see our interpreter behaves correctly on all previous examples, but this time also handles all error cases without crashing. The check-pred function checks a predicate on the computed result. Here we are checking if the last 3 programs result in an Err value.

Runtime type checking

Our language was an untyped one until now, but now because of the error handling we just added we have a runtime type-checked language, or colloquially known as a dynamically-typed language. Instead of giving us undefined behaviors on type errors (or crashes), our language now protects against type errors and fails reliably.

This is the same behavior as industrial grade languages such as Python:

> 3 + "foo"

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for +: 'int' and 'str'

Runtime type checking catches errors that happen during the evaluation of the program. Thus there is no way to know ahead of time which expression will cause a type error at runtime without running the program. This means, we can still write code ridden with type errors in a runtime type-checked language but still not be aware of it ahead of running our program. Even running our program does not flag all type errors as not all paths are taken during the execution of a program. Consider the example program in our Defend language:

(if (zero? (sub1 1)) (+ 2 3) (add1 #f))

This program has a type error in the else-branch of the if, but it will never be caught while running the program. The if will always evaluate to #t and go to the then-branch.

Static type-checking is an alternative way to address this problem. It can catch type errors in the program without running it, thus it can flag errors in parts of the program that you might not have evaluated when testing it. We will look at static type-checking later in the semester to compare the strengths and weaknesses of the approach in details.