Arithmetic: Calculating Numbers

Table of contents

Refining the Amount Language

We have seen all the essential pieces of a language (a grammar, an AST data type definition, operational sematics, an interpreter, and some correctness tests) for implementing a programming language, although for a very simple one.

We will now, through the process of iterative refinement grow the language to be more useful by designing more features.

We will add arithmetic operations to Amount, such that we can now increment, decrement numbers as well as do arithmetic operations such as addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. We will call this new language Arithmetic. It is still a very simple language, but atleast our programs will compute something.

Concrete syntax for Arithmetic

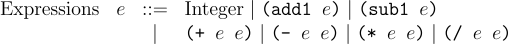

Arithmetic extends Amount to have some unary and binary operations. It contains the #lang racket line followed by a single expression. The grammar of concrete expressions is:

So 42, -8, 120 are all valid programs now. But so are programs like (add1 42), (+ 43 (add1 23)).

An example of a concrete program:

#lang racket

(+ 43 (- (add1 23) (sub1 -8)))

Abstract syntax for Arithmetic

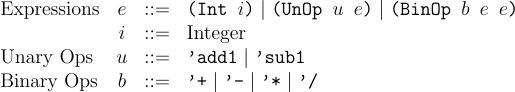

The grammar of abstract Arithmetic expressions are:

So just like (Int 42), (Int -8), and (Int 120) are all valid ASTs, so are (UnOp 'add1 (Int 42)) and (BinOp '+ (Int 43) (UnOp 'add1 (Int 23))).

We can define these data types for representing expressions as:

#lang racket

;; arithmetic/ast.rkt

(provide Int UnOp BinOp)

;; type Expr =

;; | (Int Integer)

;; | (UnOp u Expr)

;; | (BinOp b Expr Expr)

;;

;; type UnOp = 'add1 | 'sub1

;; type BinOp = '+ | '- | '* | '/

(struct Int (i) #:prefab)

(struct UnOp (u e) #:prefab)

(struct BinOp (b e1 e2) #:prefab)

The parser is more involved that Amount, but still straightforward:

#lang racket

;; arithmetic/parse.rkt

(provide parse)

(require "ast.rkt")

;; S-Expr -> Expr

(define (parse s)

(match s

[(? integer?) (Int s)]

[(list (? unop? o) e) (UnOp o (parse e))]

[(list (? binop? o) e1 e2) (BinOp o (parse e1) (parse e2))]

[_ (error "Parse error")]))

;; Any -> Boolean

(define (unop? x)

(memq x '(add1 sub1)))

;; Any -> Boolean

(define (binop? x)

(memq x '(+ - * /)))

Meaning of Arithmetic Programs

The meaning of Arithmetic programs depends of the form of the expression:

- The meaning of the integer literal is the just the integer itself;

- The meaning of the the increment expression (

add1) is one more than the subexpression; - The meaning of the the decrement expression (

sub1) is one less than the subexpression; - The meaning of the the addition expression (

+) is the sum of two subexpressions; - The meaning of the the subtraction expression (

-) is the difference between the first and second subexpressions; - The meaning of the the multiplication expression (

*) is the product of the two subexpressions; - The meaning of the the division expression (

/) is the result of dividing the first subexpression by the second.

Note, that Arithmetic is a language of integers, hence all operations should evaluate to integers.

The operational sematics reflects the dependence of the subexpressions as well.

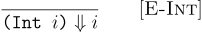

As the meaning of integers do not depend on a subexpression:

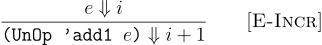

The meaning of the increment operation depends on only one subexpression:

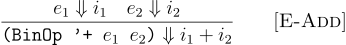

The meaning of the addition operation depends on two subexpression:

The first rule looks familiar; it’s the exact semantics of integers from Amount. The second and thirs rule are more involved. In particular they have premises over the line. If the premise is true, the conclusion below the line is true as well. These rules are conditional on the premise being true. In contrast, the first rule applies unconditionally.

The rules for sub1, -, *, and / will look similar. You should try writing those down as an exercise.

Recall that  is a relation. So we can say:

is a relation. So we can say:

- For all integers i,

(Int i)is in ;

; - For all expressions e and integers i, if

(e, i)is in then

then ((UnOp 'add1 e), i + 1)is in ;

; - For all expressions e1, e2 and integers i1 and i2, if

(e1, i1)and(e2, i2)are in then

then ((BinOp '+ e1 e2), i1 + i2)is in ;

; - … and so on!

These rules are inductive. We start from the meaning of integers and if we have the meaning of an expression, we can construct the meaning of a larger expression.

Interpreter for Arithmetic

We can translate these operational semantics rules to an interpreter:

#lang racket

(provide interp)

(require "ast.rkt")

;; Expr -> Integer

(define (interp e)

(match e

[(Int i) i]

[(UnOp op e) (interp-unop op (interp e))]

[(BinOp op e1 e2) (interp-binop op (interp e1) (interp e2))]))

;; Op Integer -> Integer

(define (interp-unop op i)

(match op

['add1 (add1 i)]

['sub1 (sub1 i)]))

;; Op Integer Integer -> Integer

(define (interp-binop op i1 i2)

(match op

['+ (+ i1 i2)]

['- (- i1 i2)]

['* (* i1 i2)]

['/ (/ i1 i2)]))

Examples:

> (interp (Int 42))

42

> (interp (Int -8))

-8

> (interp (UnOp 'add1 (Int 30)))

31

> (interp (BinOp '* (Int 2) (Int 3)))

6

> (interp (BinOp '+ (Int 43) (UnOp 'add1 (Int 23))))

67

Here’s how to connect the dots between the semantics and interpreter: the interpreter is computing, for a given expression e, the integer i, such that (e, i) is in  . The interpreter uses pattern matching to determine the form of the expression, which determines which rule of the semantics applies.

. The interpreter uses pattern matching to determine the form of the expression, which determines which rule of the semantics applies.

- if e is an integer

(Int i), then we’re done: this is the right-hand-side of the pair(e, i)in .

. - if e is an expression

(UnOp 'add1 e), then we recursively use the interpreter to compute i such that(e, i)is in . But now we can compute the right-hand-side by adding

. But now we can compute the right-hand-side by adding 1to i. - if e1 and e2 are expressions

(BinOp '+ e1 e2), then we recursively use the interpreter to compute i1 and i2 such that(e1, i1)and(e2, i2)are in . But now we can compute the right-hand-side by adding i1 to i2.

. But now we can compute the right-hand-side by adding i1 to i2.

This explanation of the correspondence is essentially a proof by induction of the interpreter’s correctness:

Interpreter Correctness: For all expressions e and integers i, if e

i, then the interpreter (interp e) equals i.

Correctness

We can turn the examples we have above into automatic test cases to verify our interpreter is correct. We will reuse the chec-interp function from Amount.

> (define (check-interp e)

(check-eqv? (interp (parse e))

(eval e)))

To turn this into an automatic test case:

(module+ test

(check-interp 42)

(check-interp -8)

(check-interp '(add1 30))

(check-interp '(* 2 3))

(check-interp '(+ 43 (add1 23))))

The problem, however, is that generating random Arithmetic programs is less obvious compared to generating random Amount programs (i.e. random integers). Randomly generating programs for testing is its own well studied and active research area. To side-step this wrinkle, here is a small utility for generating random Amount programs, which you can use, without needing the understand how it was implemented. Don’t worry, you will not be asked to write programs like this in the exam or assignments.

(define (random-expr)

(contract-random-generate

(flat-rec-contract b

(list/c 'add1 b)

(list/c 'sub1 b)

(list/c '+ b b)

(list/c '- b b)

(list/c '* b b)

(list/c '/ b b)

(integer-in #f #f))))

Calling (random-expr) now will produce random programs from our grammar:

> (random-expr)

'(/ (- (- (+ 17 1) (+ 2 -2)) (+ (* 1 -5) (sub1 -4))) (sub1 0))

> (random-expr)

'(add1 (sub1 -3))

> (random-expr)

'(sub1 (/ (- (/ -2 0) (+ 5 1)) (/ (/ 4 1) 2)))

> (random-expr)

'(* (* (* 4 (* 4 -8)) 5) (* (add1 (- -2 2)) (+ 2 (sub1 -3))))

> (random-expr)

'(add1 (add1 (+ 0 (add1 3))))

You can run this in a loop to check if our Arithmetic language interpreter complies with Racket semantics:

> (for ([i (in-range 100)])

(check-interp (random-expr)))

At this point we have not found any counter-example to interpreter correctness. It’s tempting to declare victory. But… can you think of a valid input (i.e. some program) that might refute the correctness claim?

Think on it.