Amount: A Language of Numbers

Table of contents

Overview

An interpreter is a single component of a programming language. So if you want to make an interpreter, you have to settle on the programming language you want to evaluate.

The specification of a programming language consists of two parts:

- Syntax: that defines the form of programs

- Semantics: that define the meaning of programs

Syntax, while important is a fairly superficial aspect of programming languages. The real heart of a programming language is its semantics and we will spend more time concerned with this aspect.

There are a few ways in which the meaning of language is specified:

- By example

- By informal description

- By reference to an implementation, often an interpreter

- By formal (mathematical) defintions

Each approach has it’s strengths and weaknesses. Examples are easy to understand, but they are incomplete and can get complicated for complex program behaviors. Informal descriptions on the other hand can be intuitive, but can be open to interpretation and ambiguity. Reference implementations provide precise, executable specifications but may over specify the language details by tying them to the implementation artifacts. In some cases, we might not have a reference implementation readily available. Lastly, formal definitions can balance both precision and under-specification, but require detailed definitions and training to understand.

For this class, we will use a combination of each wherever possible.

To begin, let us start with a very small language: Amount. The only kind of expression in Amount are integer literals. Running an Amount program produces that integer. Simple, innit?

Concrete syntax for Amount

We will simplify matters of syntax by using the Lisp notation of s-expression for the concrete form of program phrases. The job of a parser is to construct an abstract syntax tree from the textual representation of a program. We will consider parsing in two phases:

- the first converts a stream of textual input into an s-expression, and

- the second converts an s-expression into an instance of a datatype for representing expressions called an AST.

For the first phase, we rely on the read function to take care of converting strings to s-expressions. In order to parse s-expressions into ASTs, we will write fairly straightforward functions that convert between the representations.

Amount, like many of the other languages studied in this course, is designed to be a subset of Racket. This has two primary benefits:

- the Racket interpreter can be used as a reference implementation of the languages we build, and

- there are built-in facilities for reading and writing data in the parenthezised form that Racket uses, which we can borrow to make parsing easy.

The concrete form of an Amount program will consist of, like Racket, the line of text:

#lang racket

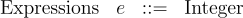

followed by a (concrete) expression. The grammar of expressions is very simple:

So, 0, 120, -42, etc. are concrete Amount expressions and a complete Amount program looks like this:

#lang racket

42

Reading Amount programs from ports, files, strings, etc. consists of reading (and ignoring) the #lang racket line and then using the read function to parse the concrete expression as an s-expression.

Abstract syntax for Amount

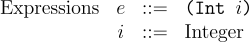

While not terribly useful for a language as overly simplistic as Amount, we use an AST datatype for representing expressions and another syntactic categories. For each category, we will have an appropriate constructor. In the case of Amount all expressions are integers, so we have a single constructor, Int.

A datatype for representing expressions can be defined as:

#lang racket

;; amount/ast.rkt

(provide Int)

;; type Expr = (Int Integer)

(struct Int (i) #:prefab)

The parser for Amount checks that a given s-expression is an integer and constructs an instance of the AST datatype if it is, otherwise it signals an error:

#lang racket

;; amount/parse.rkt

(provide parse)

(require "ast.rkt")

;; S-Expr -> Expr

(define (parse s)

(match s

[(? integer?) (Int s)]

[_ (error "Parse error")]))

Meaning of Amount programs

Even though the semantics for Amount is obvious, we can provide a formal definition using operational semantics.

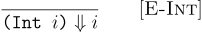

An operational semantics is a mathematical definition that characterizes the meaning of programs. We will defined the semantics of Amount as a binary relation between programs and their meanings. So in the setting of Amount, this binary relation will be a set of pairs of expressions and integers. This relation will be defined inductively using inference rules. For such a simple language, just a single inference rule suffices:

Here, we are defining a binary relation, called  , and saying every integer literal expression is paired with the integer itself in the relation. So (Int 2)

, and saying every integer literal expression is paired with the integer itself in the relation. So (Int 2)  2 holds, (Int 5)

2 holds, (Int 5)  5 holds, and so on.

5 holds, and so on.

The inference rules define the binary relation by defining the evidence for being in the relation. The rule makes use of meta-variables drawn from the non-terminals of the language grammar. A pair is in the relation if you can construct an instance of the rule (substituting some integer for i) in the rule.

(This part probably seems opaque at the moment, but it will become clearer as we work through more examples, so don’t worry.)

The operational semantics defines the meaning of Amount programs. The intepreter computes that meaning. We can view the semantics as a specification, and the interpreter as an implementation.

Characterizing the correctness of the interpreter boils down to the following statement:

Interpreter Correctness: For all expressions e and integers i, if e

i, then the interpreter (interp e) equals i.

We now have a complete (if overly simple) programming language with an operational semantics. Now let’s write an interpreter.

An Interpreter for Amount

We can write an “interpreter” that consumes an expression and produces it’s meaning, i.e., a translation of the operational semantics to code:

#lang racket

;; amount/interp.rkt

(provide interp)

(require "ast.rkt")

;; Expr -> Integer

;; Interpret given expression

(define (interp e)

(match e

[(Int i) i]))

Examples:

> (interp (Int 42))

42

> (interp (Int -8))

-8

We can add a command line wrapper program for interpreting Amount programs saved in files:

#lang racket

(provide main)

(require "parse.rkt" "interp.rkt")

;; String -> Void

;; Parse and interpret contents of given filename,

;; print result on stdout

(define (main fn)

(let ([p (open-input-file fn)])

(begin

(read-line p) ; ignore #lang racket line

(println (interp (parse (read p))))

(close-input-port p))))

The details here aren’t important (and you won’t be asked to write this kind of code), but this program reads the contents of a file given on the command line. If it’s an integer, i.e. a well-formed Amount program, then it runs the intepreter and displays the result.

For example, interpreting the program 42.rkt shown above:

> racket -t interp-file.rkt -m 42.rkt

42

But is it Correct?

At this point, we have an interpreter for Amount. But is it correct?

Recall the statement for interpreter correctness, which states our interpreter will capture the operational semantics of Amount. Though proving this is an interesting endeavour, however, from a practical standpoint we can use the other ways of specifying the language’s behavior to check our interpreter for Amount does what we expect it to do. Since we can run the interpreter (unlike the operational semantics), we can test it on multiple inputs to see if our interpreter is correct.

One of the ways to specify the meaning of programs is through examples. We can turn this into tests. For Amount, the output of the program is the program itself.

> (check-eqv? (interp (parse 42)) 42)

> (check-eqv? (interp (parse 37)) 37)

> (check-eqv? (interp (parse -8)) -8)

We can go one step further. Another way to specify programs is to check if it is in compliance with a reference interpreter. As the language we just built, Amount, is a subset of Racket we can also run amount programs in Racket. In other words, given a Amount program, if our interpreter agrees with Racket, we have a correct interpreter.

We have the following equivalence:

(interp (parse e)) equals (eval e)

where eval runs a program in the Racket interpreter.

We can turn this in a property-based test, i.e. a function that computes a test expressing a single instance of our interpreter correctness claim:

> (define (check-interp e)

(check-eqv? (interp (parse e))

(eval e)))

> (check-interp 42)

> (check-interp 37)

> (check-interp -8)

This is a powerful testing technique when combined with random generation. Since our correctness claim should hold for all Amount programs, we can randomly generate any Amount program and check that it holds.

> (check-interp (random 100))

> (for ([i (in-range 10)])

(check-interp (random 10000)))

The last expression is taking 10 samples from the space of Amount programs in [0,10000) and checking the interpreter correctness claim on them. If the claim doesn’t hold for any of these samples, a test failure would be reported.

Finding an input to check-interp that fails would refute the interpreter correctness claim and mean that we have a bug. Such an input is called a counter-example.

On the other hand we gain more confidence with each passing test. While passing tests increase our confidence, we cannot test all possible inputs this way, so we can’t be sure our interpreter is correct by testing alone. To really be sure, we’d need to write a proof, but that’s beyond the scope of this class.